A Brief Primer on the United States Postal Service's Distribution Network

The oldest distribution network in the United States has been getting a pretty radical facelift since 2021

The United States Post Office famously started in 1775, with Benjamin Franklin as Postmaster General, but it only became an independent organization, the United States Postal Service, on July 1, 1971 after the Postal Reorganization Act. On that same day, the American Postal Workers Union (APWU) was founded from the merging of five postal unions.

The creation of USPS was about many things, but the key one was that the Post Office Department had begun running a huge deficit in the 1960s and also had real problems keeping up with volume. Not wanting to deal with the political costs, Nixon and others thought it sound to set up postal service on its own footing - free to raise rates (within certain limits, and as approved by the Postal Regulatory Commission), modernize and reorganize service, etc. with less congressional oversight.

Despite being freer to raise prices in line with costs, USPS was and is still subject to the “universal service obligation” (USO) to provide postal service a) to everyone and b) at an affordable price. As Trump and others hold the threat of USPS privatization over our heads, Amazon in particular is racing to build out its rural distribution capacity to make a credible case that it can meet this USO (though, as I argue here, it’s still way behind UPS in this regard).

In 2021, Postmaster General Louis DeJoy announced Delivering for America (DFA), a ten-year comprehensive modernization plan. DeJoy resigned in March 2025, though DFA modernization appears to be continuing on. In what follows, I am going to describe USPS’s network within the DFA framework, as that appears, right now, to be the framework that postal service will progressively be fit within as time goes on. But it should be kept in mind that this process is ongoing, and that some facilities that have been announced to be serving a new function within DFA’s network configuration are still basically doing what they’ve traditionally done.

As with all of our brief primers, this one comes with a map of USPS’s distribution network. Special thanks to Steve Hutkins at savethepostoffice.com. This map would not have been possible without his diligent information gathering and generosity in sharing data.

The DFA Plan

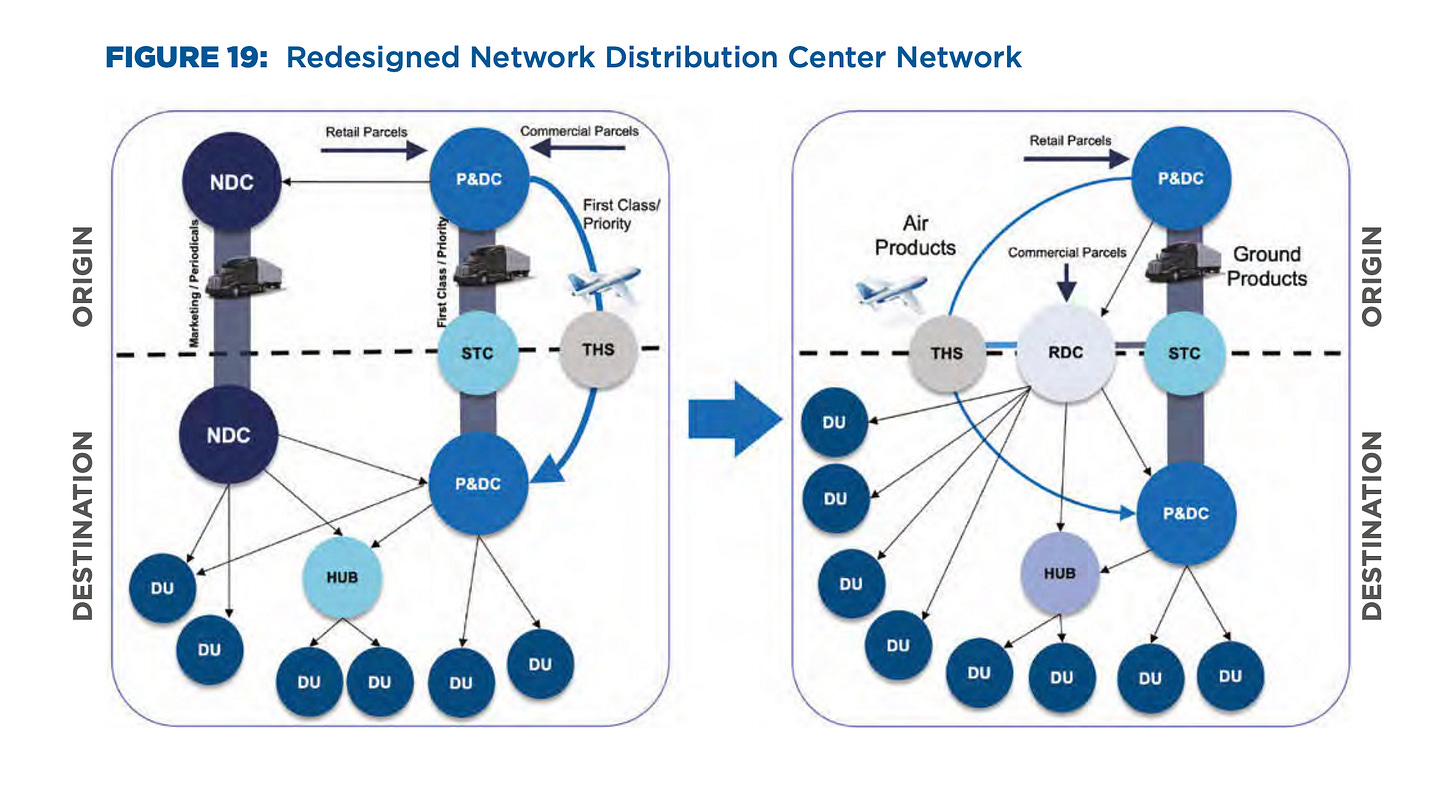

DFA aims to do a lot of different things; the full plan is here. I’m only going to focus in particular on what it aims to do for USPS’s distribution network, which was originally laid out in this graphic:

Before DFA, the 250 Processing and Distribution Centers (P&DC) were the primary distributional nodes of USPS. They were aided by 21 Network Distribution Centers (NDC) for marketing mail, periodicals, and packages. There were also a variety of smaller facilities - Processing and Distribution Facilities (P&DFs), Mail Processing Annexes (MPAs), Logistics and Distribution Centers (L&DCs) - all of which either dealt with P&DC overflow or specialized parts of the distribution network. Finally, there are the Delivery Units, which are primarily the back-of-house, last-mile carrier operations at post offices. Of the 32,500 USPS-operated post offices (as opposed to the few thousand contractor-operated ones), about 19,000 have Delivery Units (DUs) - though that number is going down all of the time with the SDC/Spoke rollout described below.

In terms of its distribution network, the goals of DFA include:

Integrating the P&DC and NDC facilities into mega-hub Regional Processing and Distribution Center (RPDC) facilities that are aided downstream by smaller Local Processing Centers (LPC). The RPDCs and LPCs are mostly converted and upgraded P&DCs and NDCs, but some are new facilities.

Eliminating many DUs through the consolidation of carrier operations into larger Sorting and Delivery Centers (SDCs) that are fed by “Spoke” facilities, i.e. post offices that give up their Delivery Units and just feed the regional SDCs. (It’s a bit confusing to describe a “spoke” as a facility that has given up its last-mile function, but that’s how it’s done in USPS world.)

The original ambition of the DFA was to “touch almost 500 network mail processing locations; 10,000 delivery units; 1,000 transfer hubs; and almost 100,000 carrier routes.” That would have been a massive overhaul. Since then the scope has been reduced significantly: the second year DFA report implies that the end goal would be between 240-300 SDCs, resulting in 3,000 Spokes.

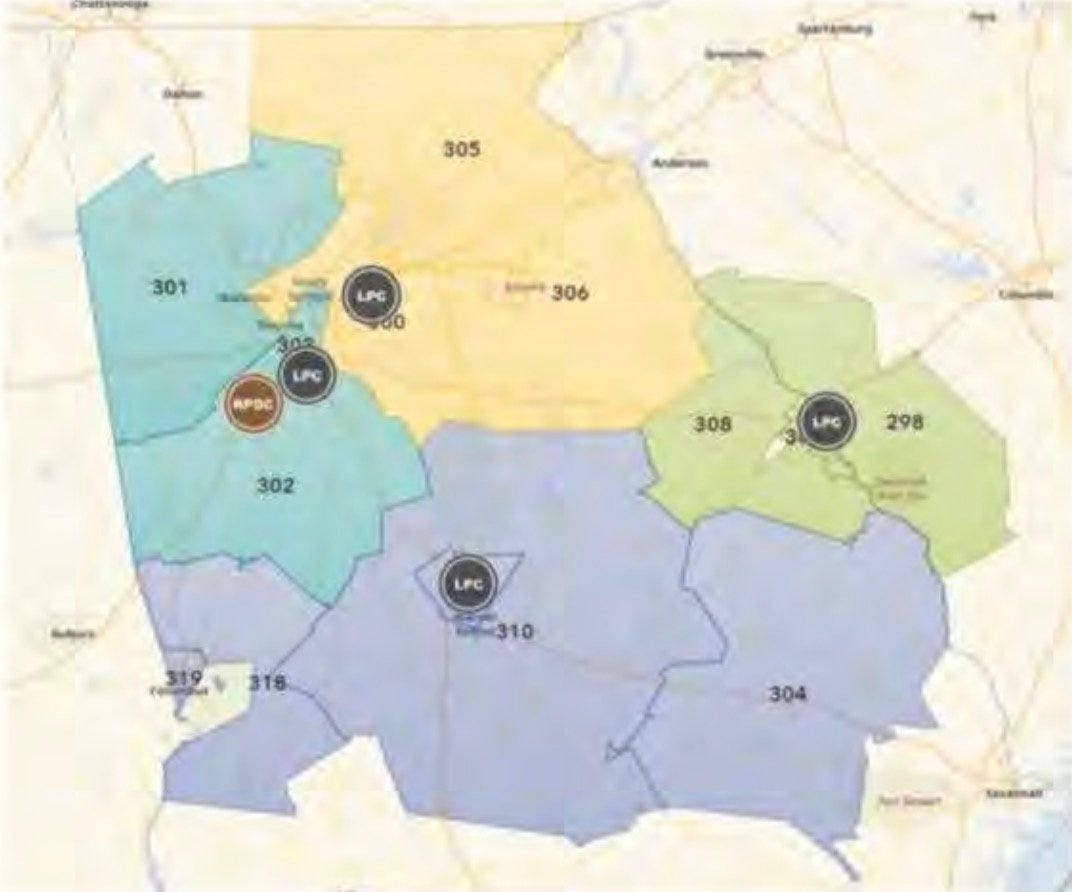

So in the revised vision, there will eventually be about 60 RPDCs, 200 LPCs, 300 SDCs, and still 16,000 DUs. Right now, there’s about 11 functional RPDCs, 31 LPCs, 100 SDCs, and 300 Spokes, meaning 300 post offices (of the original 19,000) have lost their DUs.

Regional Processing Distribution Centers (RPDCs), Local Processing Centers (LPCs), and Transfer Hubs

The “backbone” of the new DFA system are the Regional Processing and Distribution Centers (RPDCs). They are/are going to be the primary sortation hubs in USPS’s system. For the most part, these facilities are repurposed P&DCS or NDCs, outfitted with new equipment, but sometimes they’re new facilities. Again, about 11 are operational as of the present, but most of the RPDC sites have already been chosen.

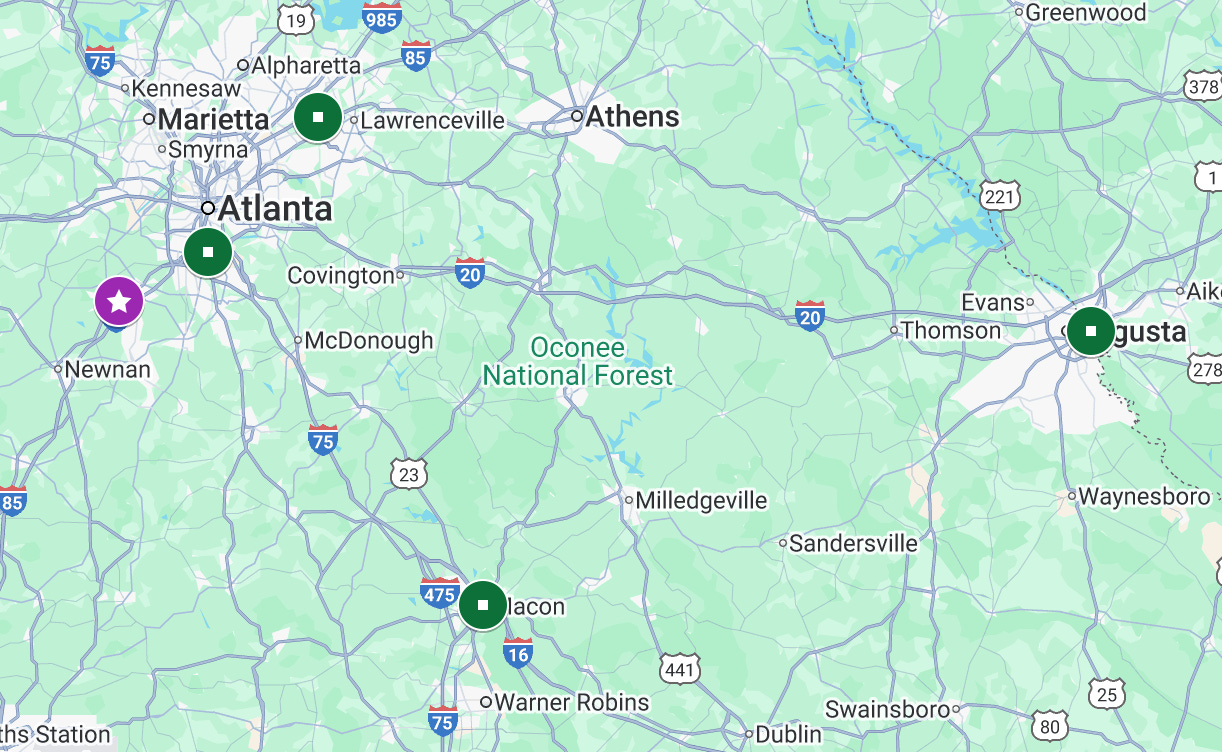

The plan is to have about 60 total, one for each region of the United States - regions being defined as areas delimited by 3-digit zip code prefixes (described in more detail here). Here’s the Atlanta region, with RPDCs and LPCs:

The Local Processing Centers sort letters and flats for SDCs and DUs from RPDCs. So here, mail from the RPDC in Palmetto, GA would be sorted and sent to the four LPCs in Atlanta, Duluth, Macon, and Augusta for sorting to last-mile facilities. LPCs will also function as package cross-docking facilities.

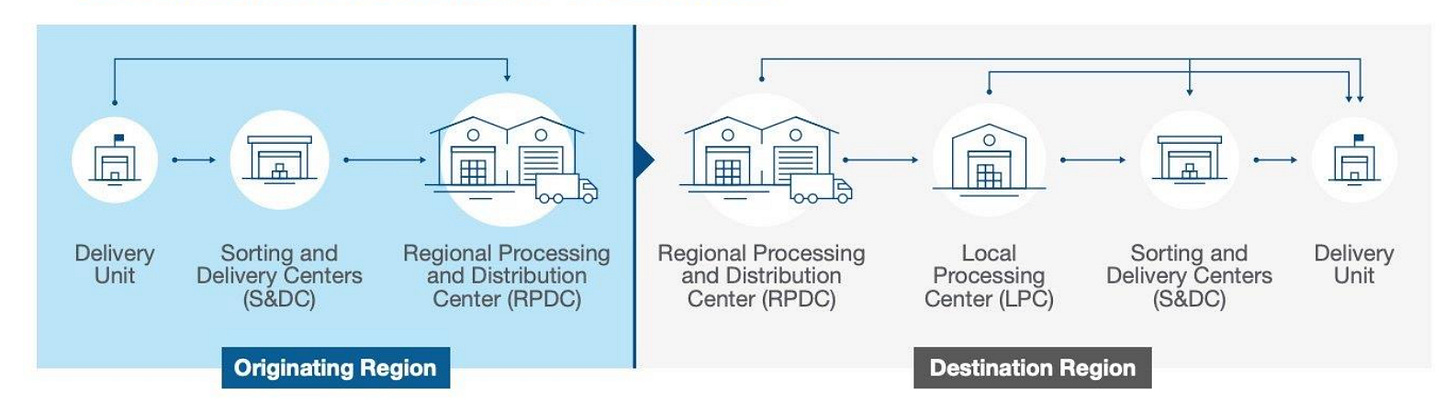

Here’s USPS’s more technical description of RPDCs and LPCs:

RPDCs will perform originating sortation operations for letters, flats, and packages to the 3-digit ZIP Code level, for dispatch to the rest of the country. RPDCs will engage in cross-docking and sortation operations for destinating letters, flats, and parcels for dispatch to a LPC…. LPCs will handle destinating letter, flat, and package sortation operations for designated 3-Digit ZIP Codes within a region, for dispatch to Sorting and Delivery Centers (S&DCs) and delivery units. LPCs may also sort and/or cross-dock carrier route bundles of flats to S&DCs and delivery units.

The Transfer Hubs (listed in the same layer as the SDCs on the map) deliver mail to individual DUs outside of the range of SDCs.

Sorting and Delivery Centers (SDCs), Spoke Facilities, and Delivery Units (DUs)

At the last-mile level, the DFA plan is to consolidate Delivery Unit functions in larger Sorting and Delivery Centers. Thus, instead of picking up the mail for their route at the Delivery Unit attached to their local post office, mail carriers will instead travel to an SDC to pick up mail for their route. Again, any post offices that have given up their back-of-house carrier functions are referred to as “Spokes,” i.e., spokes of the “hubs” that are the SDCs. These facilities will mostly remain as retail locations, but some will probably close, and in any event there will be less need for as many postal workers.

Moving delivery operations to SDCs makes a lot of sense from the perspective of network efficiency: if you are familiar with the last-mile operations of UPS (745 Package Centers), FedEx (689 Ground Facilities), or Amazon (601 Delivery Stations), you’re probably shocked to find out that USPS has 19,000 of them. And no doubt part of the idea behind DFA is to make USPS’s last-mile network more efficient by eliminating some (originally 6,000, but now more like 3,000) of them.

From the standpoint of mail carriers, however, this is a huge pain in the ass, adding a lot of time to their commutes. Hutkins estimates that with 17 mail routes per DU, about 50,000 routes will be relocated with the creation of 3,000 Spokes. That said, even if DFA hits its revised target goals, there will still be 16,000 Delivery Units, so this is, for the moment, far from a complete overhaul of USPS’s last-mile operations.

I listed the Spoke Facilities on the map, but it should be kept in mind that these are facilities that have lost their last-mile functions. I mostly didn’t include the Delivery Units themselves because there are so many of them, and Google Maps only allows 2,000 locations per layer.

But I did including the DUs for the least populous state in the country, Wyoming, just so you can see the scale of USPS’s coverage. USPS currently has 77 last-mile facilities in Wyoming. UPS has 9, FedEx has 8, and Amazon has 2. Keep these numbers in mind should postal privatization proceed. It’s likely that any company that took over postal service would radically reduce last-mile facilities (even if they kept the retail “Spoke” locations), resulting in more headaches for carriers and massive service coverage delays and lapses.

Regional Transportation Optimization and the Future of DFA

In February 2025, USPS initiated Regional Transportation Optimization (RTO), against the advice of the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC), which supposedly oversees USPS operations. RTO is pretty simple: it aims to end late afternoon collections at 3/4 of the nation’s post offices. Rather than being transported to P&DCs for overnight processing, mail will simply sit until the next morning, adding a day or two to delivery times. So far, about 10,000 post offices have lost afternoon collection.

USPS and the PRC are at odds over this cost cutting initiative but also about the entirety of DFA restructuring. In September 2023, the Commissioner of the PRC described DFA as “the most fundamental change to the network since Ben Franklin was the postmaster general.” And in March of this year, they described DeJoy and DFA as having “failed miserably” to improve postal service.

Perhaps, with DeJoy out, this will mean a reversal of DFA plans. Unfortunately, I could also see PRC criticisms of DFA playing into the schemes of DOGE-types to further reduce USPS service or push for privatization.