A Brief Primer on Berkshire Hathaway's Industrial Footprint

Its top four subsidiaries together have an industrial footprint bigger than that of Target

In the 2000s, the labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein proposed the idea that Walmart was the “template organization” of neoliberal capitalism, something like what GM was for Fordist capitalism. I think there’s good reason to follow him in saying this, but I might suggest instead the multinational conglomerate holding company Berkshire Hathaway for this role.

In fifty years time, I can only hope that historians look back in puzzlement at the existence of this company and wonder about very basic questions regarding it. Walmart sells everyday items. UPS delivers packages. Amazon does both. How might one describe the use-value of Berkshire Hathaway in simple terms? What does the phrase “multinational conglomerate holding company” really signify other than “a bunch of random things tied together by nothing but the pursuit of profit”?

That’s why I think it’s a good candidate for “template organization of contemporary capitalism”: it’s a rather unique organizational manifestation of the abstraction of exchange-value.

That said, Berkshire Hathaway does buy up whole businesses, rather than just partially invest in them, and many of those businesses have a pretty expansive physical footprint in the country. They’re the eighth largest employer in the US, just ahead of CVS. For an abstract company, it has a very concrete physical presence.

Most of my brief primers have been on the distribution networks of large employers, but I figured it might be useful to cover Berkshire Hathaway’s entire industrial footprint in this primer, given the diversity of their investments and wanting to see if anything interesting comes of taking a wider view. And as with all of the brief primers, this one comes with a map, in this case of all the industrial properties of Berkshire Hathaway subsidiaries in the United States.

Below are the top nine Berkshire Hathaway wholly-owned subsidiaries in terms of total square feet of industrial space according to CoStar.

These top nine companies account for about 30% of Berkshire Hathaway’s total revenue, and they occupy about 87 million square feet of industrial space altogether. The rest of Berkshire Hathaway’s 320 industrial properties have only a little less than 26 million square feet. Together the top four here occupy a little over 67 million square feet, which is bigger than Target’s industrial footprint of more than 66 million square feet.

The big five include three manufacturing companies (Shaw, Precision Castparts, and Johns Manville), one supply chain company (McLane), and one industrial holding company (Marmon)—a holding company inside a holding company! After Johns Manville’s 11 million square feet, there’s a pretty big drop off to number 6, which is MiTek Industries at 2 million square feet.

In terms of employee counts, the top nine companies here employ a little more than 147,000 people, roughly 46% of Berkshire Hathaway’s entire workforce of 322,000 people.

The IAM has made efforts to organize Precision Castparts, including an election of 2300 PCC workers in 2013 (lost 932-1258) and an election of 100 welders in 2017 (successful, but decertified in 2022). Various articles claim that about 20% of Precision’s workforce is subject to collective bargaining arrangements, but I can’t find much more information than that. Teamsters Local 20 represents production and maintenance workers at 3 Johns Manville facilities in Ohio, and about half of the workers at a Johns Manville facility in Tennessee are represented by the Steelworkers. Shaw appears to be completely non-union.

McLane & BNSF

Since this is a newsletter about labor & logistics, it makes sense to say a bit more about two of the above companies: McLane and BNSF. McLane was acquired by Berkshire Hathaway in 2003 from Walmart, and soon thereafter it acquired other food distributors to become a major player in that segment of the supply chain. Its biggest customers are Walmart, 7-Eleven, and Yum! Brands, which accounted for 17%, 14%, and 12.3% of its revenue in 2023 respectively. There don’t appear to be any McLane facilities that are unionized.

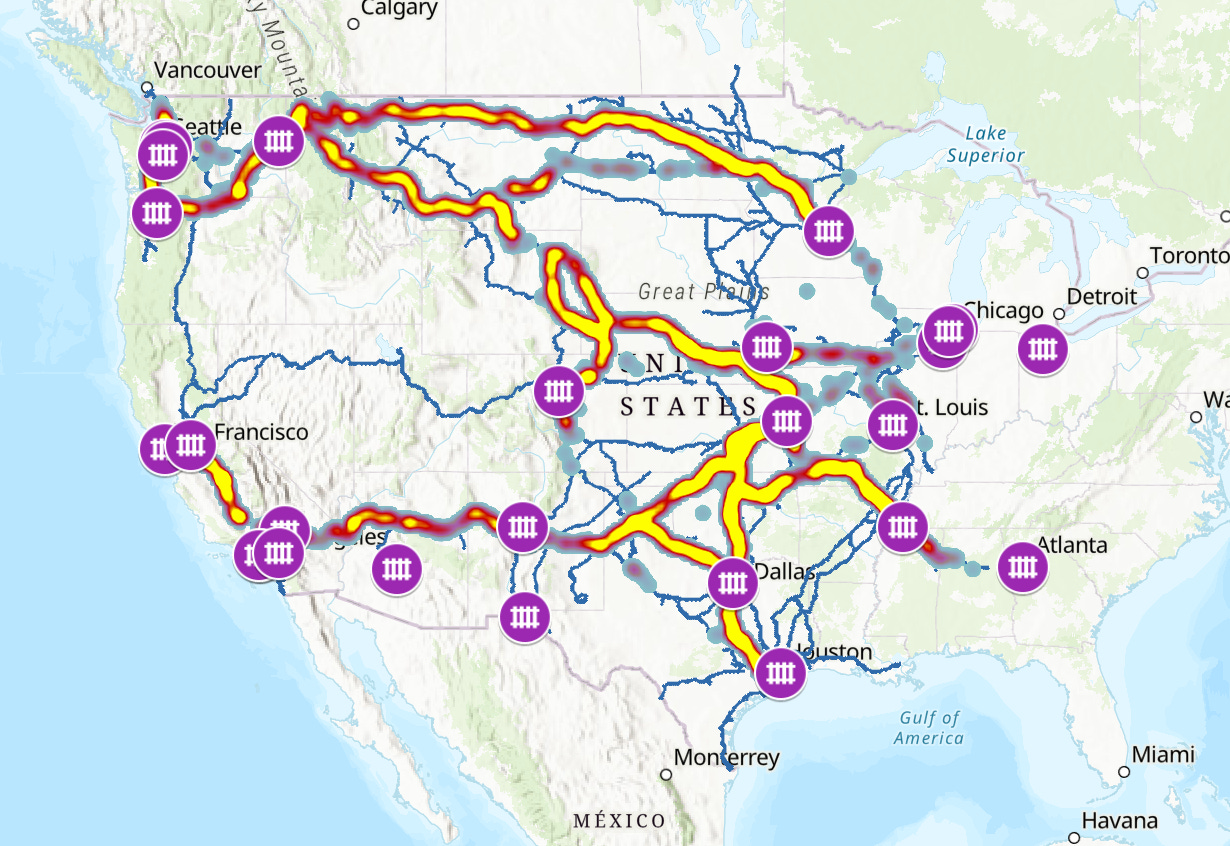

As for BNSF, what’s listed in the table above are all of the properties described as “industrial” in CoStar, but BNSF operates many other intermodal terminals around the country. Here are two maps including BNSF’s rail network, a heatmap of train activity on certain key lines, and the company’s industrial properties (first map) and its intermodal terminals (second map).

You don’t mention Fruit of the Loom, which used to have a big manufacturing network in the US southeast, and which moved in the 1980s to Central America, particularly Honduras and El Salvador. This another particularly important aspect of modern US capitalism, the offshoring of production to low-wage countries of the global south. Fruit of the Loom is now further relocating from Central America (where its factories unionized in the early 2000s) to factories in Bangladesh, Morocco and southern Mexico.