A Brief Primer on Walmart’s Distribution Network

Still the largest employer in the country after all these years...

*Updated July 30th, 2025

By revenue, Walmart is the largest corporation in the US. By employment numbers, it is as well. Year after year, it is the largest importer in the country. Nelson Lichtenstein once said that Walmart was the “template” organization for neoliberal capitalism, as GM was for the Fordist period. With the growth of e-commerce, it doesn’t quite seem that way anymore, but it is still a reigning titan by any measure.

Part of why Walmart was considered by Lichtenstein and others to be a template organization is that it embodied the broader shift from “push” to “pull” production and distribution. As Edna Bonacich and Jake Wilson describe this shift,

Under the “push” system, production was dominated by large consumer goods manufacturers. They had long production runs in order to gain efficiencies of scale and minimize unit costs…. Under the “pull” system, consumer behavior is tracked by the retailers, who then transmit these preferences up the supply chain to the producers. Manufacturers try to coordinate production with actual sales, minimizing inventory buildup anywhere in the chain by collecting data from retailers at the point of sale (POS).

This transformation entails a shift of power from manufacturers to retailers, one that Walmart in particular has put to exacting use, squeezing all part of the supply chain from its Asian manufacturing vendors to ocean carriers to 3PLs. They’ve been able to do this because a) they’re the preferred one-stop shop for millions of Americans who associate them with “everyday low prices,” b) they have a highly efficient distribution infrastructure, and c) they have accurate point of sale data that they share with suppliers through electronic data interchange (EDI).

On all of these points, Walmart is not just dominant; it was also a pioneer. Unlike Kmart, for instance, which gave individual store managers a great deal of leeway to run “blue light special” sales, Walmart focused on delivering consistently affordable products. Also unlike Kmart or Sears, it focused early on on improving its distributional capacities. And most famously it pioneered the use of the lowly barcode, which allowed it to have the POS data necessary to tame manufacturers.

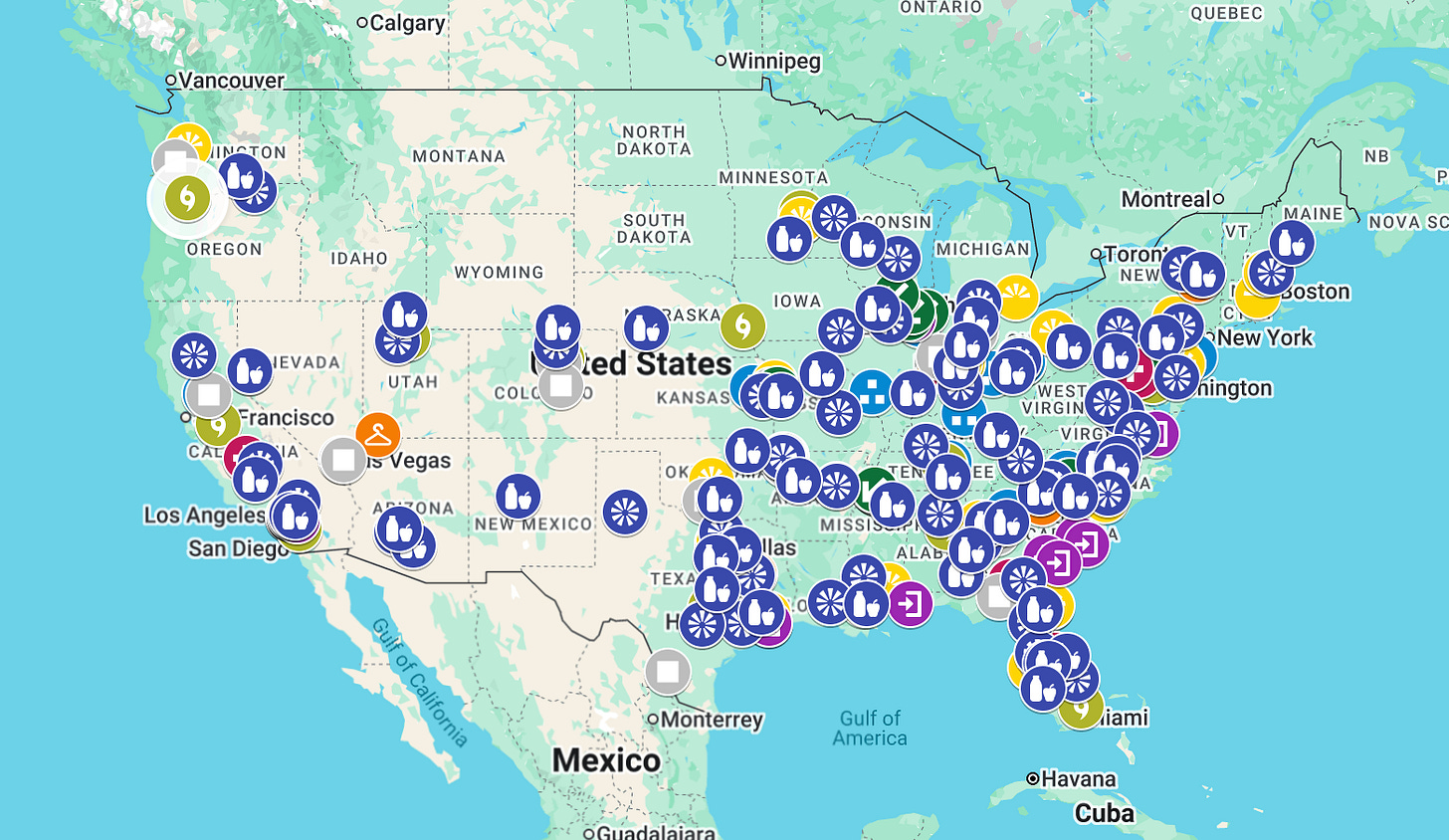

As with all of our distribution network primers, this one comes with a map of Walmart’s Distribution Network that we will do our best to keep current. Please do email us at ontheseams.newsletter@gmail.com if you have any updates.

Import Distribution Centers

Walmart has 14 Import Distribution Centers (IDCs) which serve as its goods receiving network. Like Amazon’s Inbound Cross-Docks (IXDs), the IDCs are generally close to ports/intermodal terminals, but unlike the IXDs, they also serve as storage tanks for goods until they’re needed at Regional Distribution Centers. One such facility in Baytown, TX is a whopping 4.6 million square feet! Amazon began to open larger national IXDs in 2024, as part of the build out of Supply Chain by Amazon, but none comes close to this in terms of size.

Walmart tended to use third-party logistics companies for these facilities until 2013, when there were labor organizing efforts at its facilities operated by Schneider Logistics in California and Illinois. A $21 million settlement was reached for workers at the California facilities, and the whole thing brought a round of bad press for Walmart. Workplace fissuring makes a lot of sense from a company’s perspective for certain components of a distribution network, like last-mile delivery, but for warehousing operations in efficient networks like those of Walmart or Amazon, it’s a mixed bag. Walmart has increasingly brought IDC operations in-house, though for about half of them they still use 3PLs.

Consolidation Centers

Consolidation Centers are relatively small cross-docking facilities meant to consolidate inbound domestic goods. Most are operated by 3PLs. Suppliers bring their goods to Consolidation Centers in less-than truckloads, the Consolidation Centers consolidate into full truckloads, and they’re off to RDCs. In this, they are something like the domestic equivalent of IDCs, though without the storage capacity.

What’s listed in the map are dedicated Consolidation Centers, but there are also some attached to 8 RDCs. They are small, easily incorporating into Walmart’s existing infrastructure, and eliminate a lot of inbound miles.

Regional Distribution Centers

The keystone to Walmart’s distributional efficiency are its Regional Distribution Centers (RDCs), of which Walmart operates 43. The RDCs developed by a simple method: leapfrogging out from Walmart’s headquarters in Bentonville, AR every 250 miles on average. Once the area within ~125 miles of an RDC was saturated with stores, they went and found a location roughly 250 miles away and built a new one. Amazon grew around population centers; Walmart grew from one point outwards.

RDCs generally have two primary sections: one part acts as a sortation cross-dock, transloading goods from bay doors on one side to those on the other, where loaded trucks head off straight for Walmart stores. The other part is larger and intended for storage. For those of you who have read our Brief Primer on Amazon’s Distribution Network, one thing that should be obvious by now is that Walmart is willing to hold onto things for much longer than Amazon. This allows the company to do things like buy winter gear in the summer when demand for it is low and sit on it until winter.

Each RDC supplies about 90-170 stores and employs 836 workers on average, per OSHA data. In 2017, Walmart partnered with Symbotic to test out RDC automation, and in 2021, they cemented that partnership by expressing their intention to eventually use Symbotic technology in all of their RDCs. Supposedly RDC efficiency is roughly doubled with the use of Symbotic, and predictably Walmart says that the use of the technology won’t replace “associates” while it also touts the labor cost savings involved. Here’s Symbotic in action:

On its 2024 Q3 earnings call, Walmart claimed to be handling 50% of its volume with automation, twice as much as a year prior.

Food Distribution Centers

The RDCs are general merchandise distribution centers, but they also do some dry grocery as well. But most food products are handled by separate Food Distribution Centers (FDCs), of which there are 54. Each one is around 1 million square feet and employs 730 people on average. Like the RDCs, they serve a roughly 125 mile radius. Increasingly they serve both Walmart and Sam’s Club stores. Like the RDCs, the FDCs are also split up into two main sections: one for dry goods, and one for perishables.

Walmart was an early adopter of Vocollect voice picking technology:

In 6 of the 48 FDCs, Walmart has installed Swisslog’s ASRS storage and retrieval system:

Walmart is also experimenting with a Witron system for full case distribution in at least two of its FDCs:

Sam’s Club Distribution Centers & Cross-Docks

Sam’s Club has a mix of dedicated distribution centers and smaller cross-docking facilities. Some have full case and split case picking, but they’re mostly dealing with full pallets—in one set of doors, and out the other, headed for a store. Walmart’s currently attempting to integrate its Sam’s Club and Walmart distribution networks, which they have traditionally kept separate.

E-Commerce Fulfillment Centers/Sam’s Club E-Commerce Dark Stores

To my mind, the two most interesting things happening in Walmart world from a distributional perspective are its rapid automation of its distribution centers and, relatedly, its adaptation to the e-commerce market, specifically its experiments in last-mile delivery. In one sense, Walmart is well-positioned to compete with Amazon by using its 4,700 stores (+ 800 Sam’s Clubs) as last-mile facilities: as they often brag, 90% of the US population lives within ten miles of a Walmart store. That is in one sense a huge head-start.

But efficient e-commerce and traditional retail structures are quite different. Amazon only has to build and pay for the former, while Walmart has to do both, and it’s no surprise that in the e-commerce era (roughly since 2013, when they started building e-commerce infrastructure), their margins have dropped dramatically. This chart from Jean-Paul Rodrigue helps in understanding how e-commerce can be more profitable than traditional retail.

The problem for Walmart is that they have to do many of the things Amazon is doing while also maintaining an extensive brick-and-mortar network with all the labor costs involved. That is not a fun position to be in, but they also can’t just cede e-commerce to Amazon.

To compete, they have built out their own E-Commerce Fulfillment Center network. There are 47 dedicated FCs, doing all the same things as Amazon Fulfillment Centers, and each employing 484 people on average. They also have a number of Sam’s Clubs that they’ve turned into e-commerce “dark stores” (i.e., stores that have essentially been converted into Fulfillment Centers). They also have attached FC operations to RDCs, IDCs, Fashion Distribution Centers, and even many stores, in the form of their mini-Market Fulfillment Centers (which are about ⅙ the size of an average Walmart store).

In addition, they’ve added “parcel stations” to many stores, essentially carving out a portion of the store for a Delivery Station. If the stores are really going to serve as last-mile facilities, they need to 1) be able to process orders coming in from FCs rather than its traditional distributional infrastructure and b) still operate as stores. If e-commerce orders deplete store inventory to the point where the in-store shopping experience is severely degraded, the “store as last-mile station” strategy hurts their core business—thus the need for something like a true Delivery Station.

As for last-mile delivery itself, Walmart has experimented with a few configurations, including a) partnering with rideshare companies like Uber and b) creating its own independent contractor app and driver workforce (Spark):

It’s also c) started up its own in-house delivery operation. Walmart’s GoLocal program, a delivery service for other retailers, helps them fill up extra space in their vans. Among other clients, they have roped Home Depot into the program—a very mutually beneficial relationship.

Regional Real Estate Warehouses (RREWs)

These are warehouses that stock and supply store materials - shelves, fixtures, etc. These are small warehouses, employing about 35 people each on average.

Fashion/Pharmacy/Miscellaneous Distribution Centers

Walmart runs 7 Fashion Distribution Centers. They average around 1 million square feet and employ 521 workers on average. Each one serves about 1,000 stores.

They also run a variety of Specialty Distribution Centers for pharmacy, optical, returns, electronics refurbishment, tires, appliances and a variety of other functions. In general, there is much more facility specialization in Walmart’s distribution network than in Amazon’s, the latter of which’s is all about size and weight and little else.

Sources: Edna Bonacich and Jake B. Wilson, Getting the Goods: Ports, Labor, and the Logistics Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008); Nelson Lichtenstein, The Retail Revolution: How Wal-Mart Created a Brave New World of Business (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009); “The Walmart Distribution Center Network in the United States,” MWPVL, https://www.mwpvl.com/html/walmart.html; Marc Wulfraat, in interview with Benjamin Y. Fong, September 24, 2024.