A Brief Primer on Amazon’s Distribution Network

With a Map!

*Note July 2, 2025: This primer is outdated; a new one can be found here.

Amazon has built a reputation on its fabulous speed and efficiency. For the customer, the experience is a form of modern magic: a few clicks and your desired items appear soon thereafter, sometimes within hours. An intricate network of facilities makes this magic possible; through it, Amazon is single-handedly transforming the industrial landscape of the United States. In some cases, Amazon has learned from the example of its competitors in the retail and parcel industries; in others, its distributional strategies are true twenty-first century innovations, made possible by the most sophisticated system for tracking and predicting consumer behavior ever built.

Now, you might be saying: sure, Amazon is obviously a big player, but single-handedly transforming the industrial landscape? Consider the following: in 2022 and 2023, Amazon added about 160 million square feet of space to its distribution network. As a point of comparison, that is about 10 million more square feet than the entire distribution network of Walmart, which has been building out its warehouses for more than fifty years.

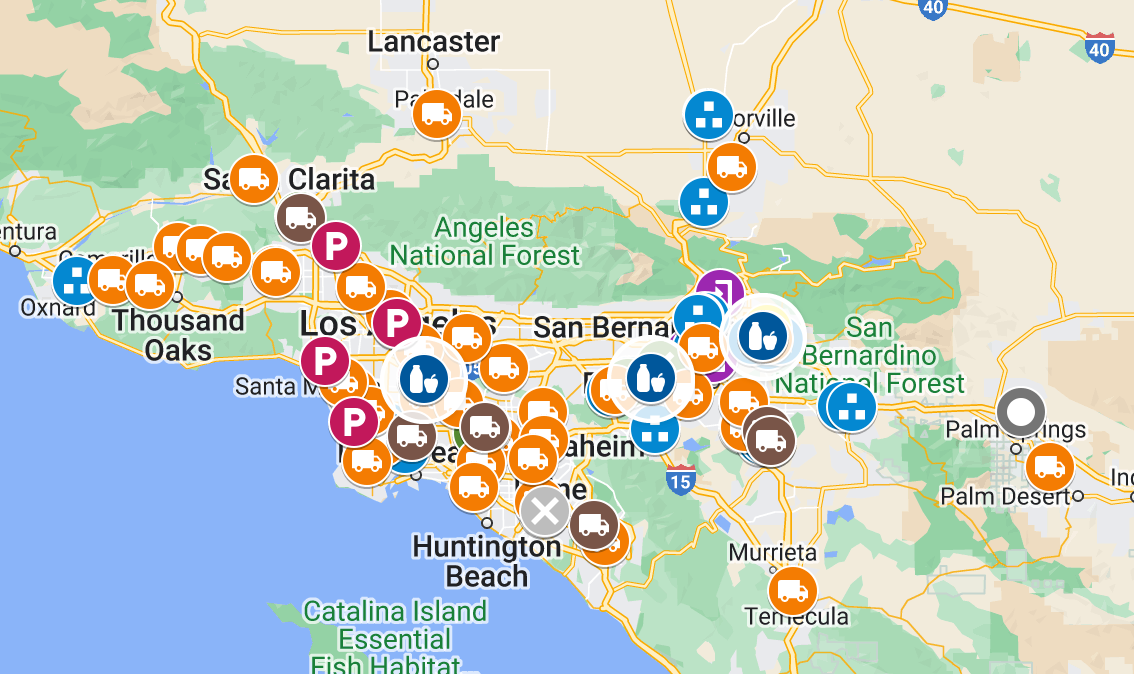

This article is meant as an introduction to Amazon’s distribution network, and it comes with a map of this network that On the Seams is doing its best to keep updated. This is a slightly easier task now that the pandemic e-commerce surge has subsided, but a fully up-to-date picture of this network would require either that you have access to Amazon data or that you have a sizable team of people whose full-time job it is to keep track of these things. We don’t have either, but we’re fairly confident in what’s here based on excellent data that MWPVL and others make publicly available, and from our own research. (While we’re here: if you have an update to this map, send us a note at ontheseams.newsletter@gmail.com.)

The map’s a little overwhelming to go through as a whole, so in the following, I’ll use the Los Angeles/Inland Empire region as an example. In addition to providing a little more space than the larger east coast markets, which are so closely packed that it can be difficult to make out what’s going on, this area is also of overriding economic importance given the volume that runs through the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and the vast tracts of warehouses of the Inland Empire (tracked here by Radical Research).

1. Inbound Cross-Docks (Purple)

The first step in the Amazon supply chain is the inbound receiving network, made up of Inbound Cross-Docking Facilities (IXDs). These facilities are naturally close to ports and rail yards. Goods are delivered to Amazon for distribution in various forms, and the whole purpose of the IXDs is to prepare items for the Fulfillment Centers (FCs), which are the next step in the chain. The FCs are meant to be highly efficient “just-in-time” environments; inventory is not meant to be there for more than a week. Thus IXDs often act as holding stations so that FCs are not overwhelmed.

“Cross-docking” is a kind of anti-warehousing arrangement pioneered by Walmart wherein bay doors are on both sides of a facility: container loads are backed into one side, and then transloaded into full truckloads on the other side. Thus, despite the fact that IXDs serve as reserve inventory for FCs, they are not intended to be like the enormous holding facilities that, for instance, Walmart has built in its import distribution centers. At the IXDs, as with any Amazon facility, the goods are not meant to hang around very long. That being said, and as we’ll cover in a future article, the Amazon inbound network is currently being reorganized as part of its regionalization strategy, resulting in qualitative changes to its IXDs.

As you can see here, all of the IXDs around Los Angeles are in the Inland Empire, and there is a preponderance of them there - roughly ¼ of all Amazon IXDs. This speaks to the enormous importance of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, through which roughly 40% of all containerized imports in the United States flow. After arriving at the ports, roughly 30% of goods are brought through the Alameda corridor (an exclusive cargo rail line) and then to the warehousing sprawl of the Inland Empire; the remaining 70% go there by truck.

2. Fulfillment Centers (Blue)

Amazon is perhaps best known in popular and academic accounts for its awe-inspiring FCs. It even gives free tours of these facilities, understanding how associated they are with the Amazon brand.

FCs are generally located in suburban/exurban areas and near major highways and parcel hubs. They employ anywhere from 1,500-3,000 “associates,” though the mega-FCs will employ upwards of 5,000 people, and employment numbers might be 50% above normal during peak season.

The FCs come in a great variety, and we will devote a separate article to FC specialization. In the popular imaginary, the commonplace referent is the small and large sortable centers: highly-automated facilities involving massive investments ($200-$500 million/per) that deal with either small sortable (things that fit in a smaller box, usually weighing less than 25 pounds) or large sortable (big boxes, but items not more than 50 pounds) packages. These are the facilities that are commonly depicted in local news clips and in Youtube videos.

One truly wild feature of these Amazon Robotics Sortable facilities is the randomized storage made possible by the army of Kiva robots deployed on each level. In a traditional warehouse, you’d want to keep all the toothbrushes grouped together with other toothbrushes and bathroom items so as to be able to find them easily. At the AR Sortable facilities, new inventory is placed randomly in the stacks carried about by the Kiva robots and bounces around the facility floor. Amazon wants there to be toothbrushes spread throughout the stacks so that when someone orders one, the nearest Kiva robot with a toothbrush in one of its stack’s pods can get to a pick station quickly. It’s a system that would have been barely imaginable just a decade ago.

In addition to these sortable facilities, there are also many non-sortable, less capital intensive fulfillment centers for bulky items like televisions and treadmills, those kinds of goods that don’t fit on conveyor belts so well. These look much more like traditional warehouses, involving lots of people moving big things around themselves. There are also specialty FCs for food, electronics, apparel, and other items.

Of the 30 facilities that can be classified as FCs pictured here, about ⅓ are for large non-sortables, and those are all in the Inland Empire. Another ⅓ could be considered those of the highly automated type of common FC depictions, and the remaining ⅓ are specialty or seasonal facilities. Some of the FCs closer to Los Angeles are SubSameDay facilities, which send their packages out directly with Amazon Flex drivers instead of to the middle- and last-mile facilities described below.

Items leave the FCs in the very packages that show up in your lobbies and on your doorsteps. To get there, some are injected into the distributional streams of the US Postal Service, the United Parcel Service, and a few regional carriers, but most (let’s say 80%, though that number is growing every day) are handled by Amazon’s own logistics operation. And from the FC, the next step in that chain is generally either an Air Hub or Sortation Center.

3. Air Hubs (Yellow)

Packages sent to Amazon Air Hubs, typically located either on or near airport property, are loaded onto Amazon Air cargo planes, where they generally go to one of a few larger hubs, including Amazon’s superhub in Hebron, Kentucky (KCVG). They then go out to other Air Hubs on their way to a Sortation Center, or directly out to a regional Sortation Center.

Without this air game, that random item that you order once and never again, which might only be stocked in a Fulfillment Center on the other side of the country, is not going to get to you in two days. So Amazon Air is key to the company’s ability to deliver on the promise of speed for their Prime customers. But sending packages on a plane is far and away the most expensive way to go, and after the pandemic splurge, Amazon realized that it needed to rein in air shipment costs.

The Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development keeps track of Amazon Air developments, and in their latest report from March 2024, they note that Amazon is simplifying their air network, reducing the number of flights but increasing overall tonnage capacity. This is a component of their much-discussed “regionalization” strategy, which again we’ll write a separate article about soon. They are also operating increasingly by a more traditional hub-and-spoke model, with Cincinnati/Wilmington growing in importance as their superhub, and Lakeland, FL and San Bernardino, CA growing as key regional hubs. At KCVG in Cincinnati and KSBD in San Bernardino, the two biggest Air Hubs, Amazon employs about 3,000 people each.

The Inland Empire is famous for its sprawl, but when it comes to Amazon facilities, the clustering around the San Bernardino and Riverside cargo airports is noticeable if you zoom in a bit. One would guess that the flow imbalance is stark, with planes leaving the area much fuller than those returning.

4. Sortation Centers (Green)

In 2014, Marc Wulfraat said that outbound transportation was Amazon’s “most significant weakness.” What a difference a decade makes. The buildout of Amazon’s “middle-mile” Sortation Centers, which sort packages and palletize them by zip code for more efficient delivery, has been key to improving Amazon’s package delivery capacity and speed, thus making it a competitor in the parcel market. Multiple FCs might be sending packages inbound, and the aim here is to get packages organized for local delivery either by Amazon Delivery Stations or by USPS. Sortation Centers seem to typically employ around 1,000 people, though some might have close to 2,500.

5. Delivery Stations (Orange and Brown)

The “last-mile” Delivery Stations are where parcels are loaded onto vans to be delivered within a roughly 45-mile service radius. They are located close to urban areas and are relatively small (between 100,000-150,000 square feet). A Delivery Station might employ 70-120 warehouse workers, and anywhere from 100-300 drivers might work out of the station (but not for the company—see below). The orange dots are the regular Delivery Stations, and the brown ones are for bulky items (coming from the FCs for large non-sortable items).

Large warehouses are situated where land and labor are cheap. Neither is the case for Amazon’s last-mile facilities, and Amazon’s “innovation” to solve the labor problem is to get different Delivery Service Providers (DSPs) to compete over contracts covering a certain volume for a Delivery Station. Sometimes 9-10 DSPs will deliver packages from a single Delivery Station. Amazon of course likes having these small companies compete for their business, and they even help Amazon employees transition into being DSP owners. The subcontracting and DSP competition allow Amazon to keep its last-mile employees at an arm’s length.

Amazon made a clear choice not only to subcontract potentially the most expensive portion of its labor force but also to stimulate small-business entrepreneurialism around its DSs. The natural difficulties of urban logistics in combination with its resistance to automation (no, widespread drone delivery to your doorstep is not happening any time soon) have made the third-party option quite appealing. For most other upstream functions, however, Amazon appears to prefer keeping its labor force in-house. Its automation game is moving fast enough to keep up with volume escalation without massively increasing its labor costs, and perhaps the example of labor unrest at third-party warehouses elsewhere (see, for instance, Schneider Logistics’ operations for Walmart in 2012) has convinced it not to go that route.

6. Prime Now Hubs (Red)

The Prime Now Hubs are located in large metro areas and are focused on the fast delivery of high-demand items. They’re relatively small (between 40-50k square feet), stock about 15,000 items or so, and unsurprisingly are located as close to dense concentrations of Prime members as possible.

7. Amazon Fresh (Blue)

These are ambient and cold storage distribution facilities for Amazon Fresh. For various reasons detailed here, Wulfraat believes that Amazon has been slow to develop its food distribution networks, but that “the next tsunami in the food industry will be Amazon.”

Sources: “Amazon Global Supply Chain and Fulfillment Center Network,” MWPVL; Jean-Paul Rodrigue, “The distribution network of Amazon and the footprint of freight digitalization,” Journal of Transport Geography 88 (2020): 1-13; Joseph P. Schwieterman and Toni Jahn, “A Tale of Two Continents,” Chaddick Amazon Air Brief No. 9, March 21, 2024; Marc Wulfraat, “Amazon is Building a New Distribution Network Quickly and Quietly,” MWPVL, July 23, 2014; Marc Wulfraat, in interview with Benjamin Y. Fong, September 24, 2024.